Reclaiming the Pin-Up: A Conversation with Hannah Rose

Posted by Emily Roach on 6th Dec 2024

Pin-up art has undergone a remarkable transformation since its mid-century heyday, evolving from male-oriented entertainment to a powerful medium for female expression. British illustrator Hannah Rose stands at the intersection of this change, bringing both scholarly insight and artistic expertise to the genre. In this wide-ranging conversation, she explores Arthur Ferrier's pioneering work, the shifting power dynamics of pin-up art, and its contemporary relevance in an increasingly conservative digital landscape.

Arthur Ferrier’s Pin-up Parade on Kickstarter. Back today!

What was your first introduction to the world of pin-up?

My first encounter with the world of pin-up was through watching old Hollywood movies when I was off school. I loved the musicals that would be broadcast during the day, and I remember being mesmerised by the glamorous Hollywood stars dancing on the screen. The costumes were dazzling, and I remember wishing I was in a musical too! Later, as a teenager, I sought out images of Gil Elvgren's work online and collected them in a folder on my computer. There was something about the bold colour combinations and the vibrant expressions of his pin-ups that drew me in. I remember dreaming of wearing full-circle skirts and red lipstick, and I don't think I've ever got past that!

Was it a subject you felt instantly drawn to? If so, why?

It absolutely was a subject I felt drawn to, and I believe it has something to do with the power I perceived these women had in their various situations. These women were often hyper-feminine, with ruby red lips, long black lashes, beautifully set hair... to be beautiful in the way they were was to be powerful, or so it seemed. I didn't notice some of the more uncomfortable messaging in the films and imagery I was looking at. I saw women expressing themselves and getting their needs met, and they were often strong-willed. I conveniently ignored the fact that these stories often ended up with the main characters getting married, or that they were driven by and often defined by their relationships to men.

It seems that a large segment, if not the majority, of modern pin-up art is made by and for women. Why do you think pin-up now has so many female fans and creators?

I think women can draw women in a way that male creators are not able to, and by creating this pin-up art, women are reclaiming it. Pin-up art created by women will often have an edge over more objectifying pin-up art created by male artists. For example, I make a conscious choice in my work not to present pin-ups in poses that are obviously positioning them as sex objects. Even though there is sexuality there, it is on the pin-ups' terms. You won't see pin-ups bent over with the 'camera' pointed up at their crotch, for example. It's very much for the female gaze, and women love seeing themselves in my work and the work of other female pin-up artists. My pin-ups are never caught with their pants down, so to speak. It's also great to send up the hyper-glamorous images I create with a crash back down to the reality of what being a woman is actually like.

How and when did you discover Arthur Ferrier? What was your first impression of his work?

I first discovered the work of Arthur Ferrier when I was about eleven years old, and my granddad gave me a book of collected comics from Blighty, I believe. I had picked it off his shelf and spent all day with it, studying the comics. At the end of the day, he gave it to me, as he could see how entranced I was by it. I pored over this book and treasured it, and I remember his work capturing my attention in a way that none of the other artists did. I would leaf through the book and stop whenever I saw a comic by Ferrier. I remember studying the way he inked vintage hairstyles and wishing that I would be able to render beautiful pin-ups the same way he did one day. The flowing linework, the innate grace of his pin-ups, the expressiveness of his characters, and the fashion were awe-inspiring. The men are often as beautifully drawn as the women, too.

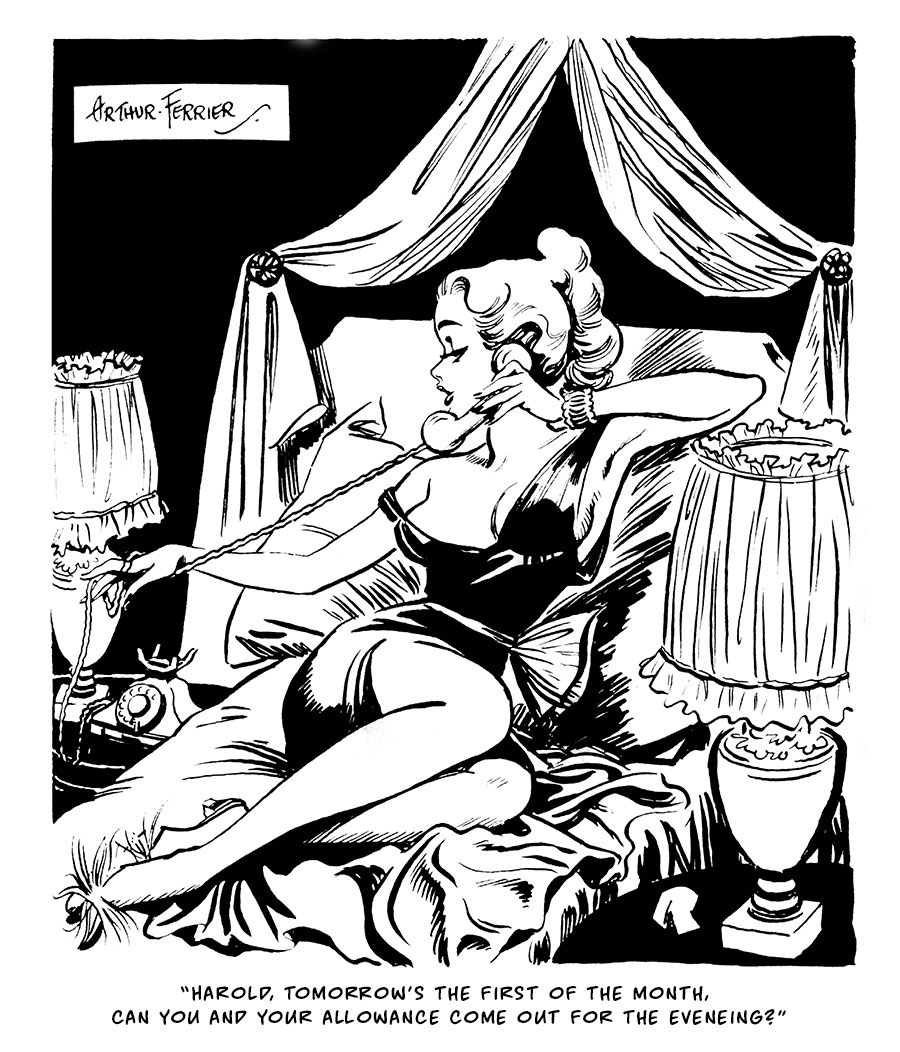

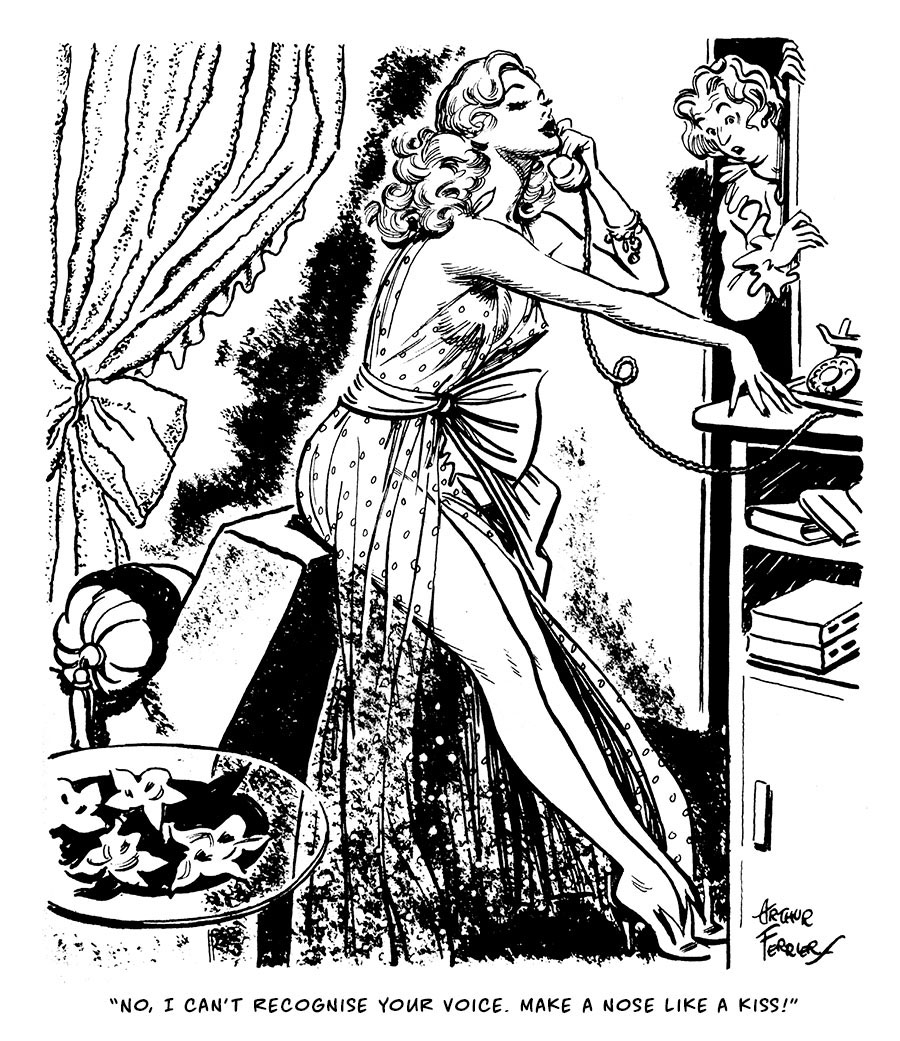

What stands out to me in this piece is Ferrier's confident use of black. It's a very balanced image, his placement of solid shadow feels effortless. How important do you think this graphic style is to his oeuvre?

I think Ferrier's use of negative and positive space is integral to his oeuvre, and this is a strong example. The solid black walls make the white areas of the pin-up and the curtains above her really pop. The curtains frame the subject beautifully, and really draw the eye to her gracefully languid pose. Solid black is utilised on her dress too, which provides a good contrast between the surrounding white areas, and ties the piece together. I love the way Ferrier renders fabric, and the overall composition and polished finish of this cartoon shows how skilled he was with ink.

Like most pin-up artists of his era, Ferrier was no stranger to boudoir illustration. Do you feel there's a power in the intimacy of such scenes, or does the gaze feel voyeuristic to our modern eye?

I do feel there's a power in capturing the intimate fantasy of these scenes, as a fantasy is primarily what they are. I see them as an insight into the idealisation of women of the time. I doubt scenes like these were all too commonplace in reality, so in a way, such images are a form of wish fulfilment. I think there is a power in these images on the part of the pin-up, as she is the one in control, however this is somewhat undermined by the often objectifying punchline. It is inherently voyeuristic, and would have been at the time too, which I venture is part of the appeal. This doesn't sit well through a modern lens, but as a cartoonist I can see ways of creating these scenes without taking the power away, and bringing the pin-up 'in on the joke', so it isn't at her expense in the same way.

You talk about the inevitability of voyeurism in these vintage illustrations - how important is it to acknowledge these prejudices with a modern lens, or can they be enjoyed despite these qualities?

I believe it's important to acknowledge the prejudices present in these vintage pin-up illustrations as you can't have one without the other. These cartoons are reflections of contemporary society, and as such will showcase attitudes and tropes that aren't as comfortable to a more modern sensibility. That being said, I tend to enjoy them because the art alone is very beautiful, though I sometimes wince at the attitudes presented. I think they can be enjoyed despite these qualities, with a healthy informed awareness of what the comics are 'saying' and the impact that had in maintaining the status quo.

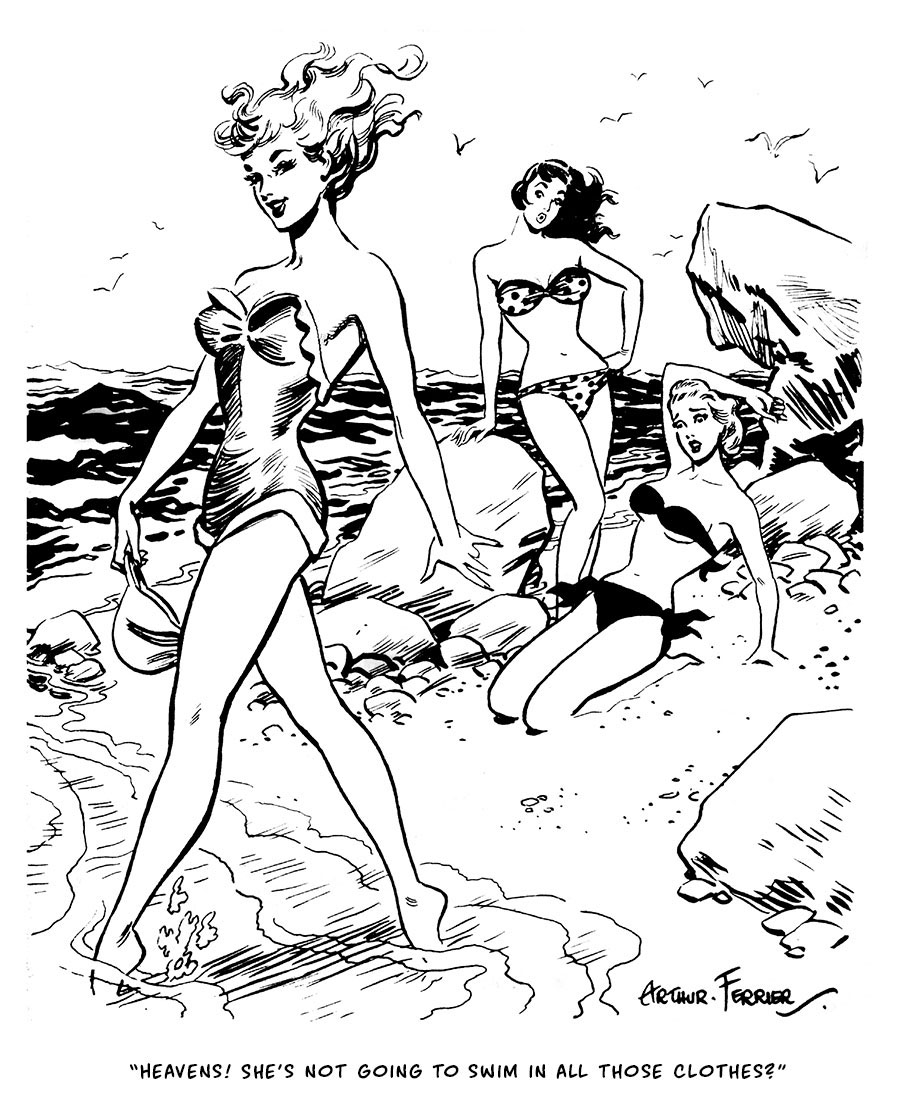

This piece shows a surprising awareness of sartorial trends on Ferrier's part with its quip about swimwear sizes. Does the emphasis on fashion in his illustrations hint at a consideration for female viewers, or is it merely a byproduct of being surrounded by female models most days?

I feel the emphasis on fashion in Ferrier's illustrations has always been present, and the focus here on swimwear shows just how exciting it was that women were wearing less at the beach. In this way, the topic is definitely still aimed at men, and sends up a common theme of women policing what other women are wearing. Norms were changing, and I saw another cartoon with two women in bikinis, but one had an issue with the other being seen not wearing lipstick, rather than her being almost nude. It's interesting if we think about this in the wider context of Blighty too. This piece is from 1954, and I have copies from 1953 that have a page featuring a male star from Hollywood, specifically 'for the ladies'. It seems that Blighty were aware of their female readership too, and I'm sure Ferrier's beautifully fashionable drawings played their part in that.

The supposedly out-of-style woman is the focus of the illustration and appears unbothered by the remarks of the more hip, bikini-clad women behind her - from a thematic point of view, it feels liberatory. Is it possible that the foundations for modern, empowering, female-led pin-up art were laid during this era, whether intentionally or not?

It certainly is possible. Although Ferrier often played to contemporary tropes and stereotypes, it wasn't always so. There are also examples of women who are in control, and who know how to handle themselves in and outside of a fight. Whether this was intended as another form of titillation or not (like Wonder Woman, who was originally a fulfilment of William Moulton Marston's kinks), these comics could definitely be viewed as an early predecessor to modern, empowering pin-up art. Just look at where Wonder Woman ended up!

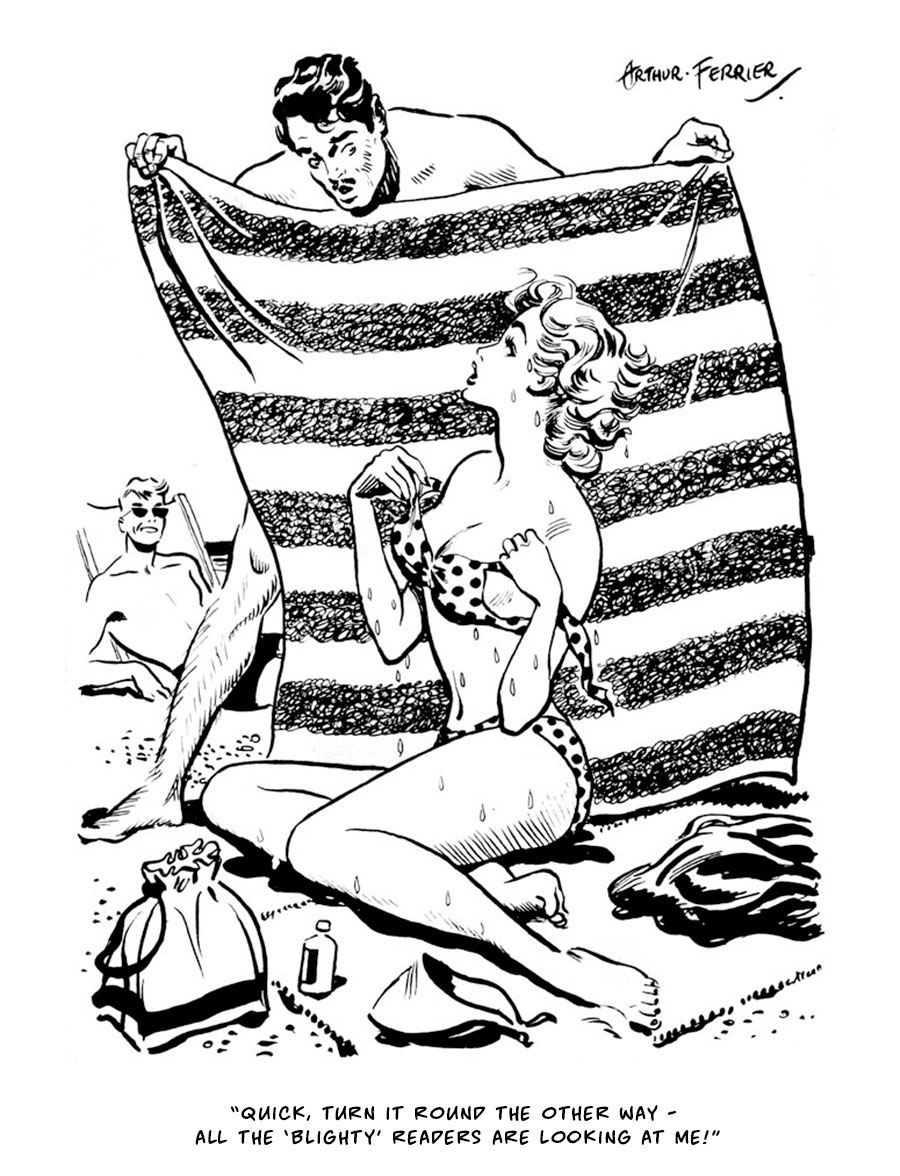

Let's talk about composition. When working in the single panel format, there's a lot of information that has to be condensed into one image; you must be economical with your design. How successfully does Ferrier draw attention to the pin-up girl, rather than the situation she's in?

Ferrier's composition is sublime in this piece, and it's the use of the towel that draws the focus to the pin-up rather than the situation she's in. The towel is a literal frame for her, and allows Ferrier to be economical with detail elsewhere in the background. Your attention is also drawn to the pin-up girl as both men are looking at her. As there's more than one man looking, Ferrier is coding the message into his work that the pin-up girl is there to be looked at, and directing the reader's eye to her. It's along the lines of not being able to resist looking at something in the sky if you see a crowd of people pointing and watching.

This piece is notable for its humorous fourth wall break, which includes the reader in the punchline. How important is humour in bringing together the dual components of pin-up, eroticism and innocence? Can pin-up work without it?

I believe pin-up can work without it, though it adds that certain extra something when it is involved. Humour can be used to empower, to deflect, and, as seen here, acknowledge the reader's probable reason for reading. This makes the comic much more immediate, and adds credibility to the comic as a result. There's a certain magic to it; if you can involve people in this way and make people laugh, they remember that. Humour also softens any tension or awkwardness on the part of the reader if they feel what they're viewing is in some way socially unacceptable. It also provides the reader with an excuse, as they could be legitimately reading for the humour rather than the scantily clad pin-ups.

Sex is inherently funny, and for the most part, fun. I think pin-up art can definitely work without humour, and be art for art's sake, but it feels different for it. Humour can provide personality and a voice, but it can also be a bit of a crutch, so personally I create a mix of jokes, and pin-up art without a punchline. I find ways to make my pin-ups 'talk' without needing to literally give them a voice with a punchline. If you take humour out of the equation, some of the innocence is lost, but then this loss of innocence can be powerful too. It's still a statement to be a woman unashamed of her sexuality, who enjoys sex, and doesn't need to deflect with humour or (assumed) innocence. I believe that's worth capturing.

In pieces like these, where the pin-up girl is toying with the lovesick men around her, Ferrier flips the traditional dynamics of seduction. How do you think this subversion of gender roles may have been received by contemporary audiences?

This is an interesting thing to consider, as there's no doubt that this piece (like the first one we looked at) is primarily a boudoir fantasy. It's clear that the woman depicted is sexually liberated, in that she must have multiple simultaneous suitors to not recognise the one with whom she is speaking. It's fascinating that a woman dating multiple men is held up as an object of desire in this way, as contemporary attitudes towards women who lived this way were not favourable. Perhaps there's something in that — society views a woman with more than one partner negatively, so she's a whore rather than a Madonna, and as such there's an element of the forbidden about feeling attracted to this pin-up. This would heighten her allure, and also posit her as 'easy'.

A recurring theme in Ferrier's work is the anonymity of male suitors. While it's usually used for humorous effect, do you think it speaks to the inherent power within female sexuality? How significant is this feeling in modern pin-up?

I feel that the anonymity of male suitors in Ferrier's work is a comment on the power of female sexuality, as it affirms his pin-ups as targets of desire, who are often dating many people. However, it could also be an example of Ferrier making suitors anonymous as a way of inviting the involvement of the reader and making the cartoon more immediate; the less detail an artist adds to a character, the more the audience will see that character as their avatar in the world of the comic. It's quite an interesting technique, as it directly invites the reader to 'become' the anonymous character. It invites the readers to put themselves in the shoes of the suitors of Ferrier's pin-ups.

I think the expression of powerful female sexuality is integral to modern pin-up, as it will always have an impact on the viewer, no matter who you are. It's attractive to see someone who is confident in themselves, and it has even more power if their body doesn't fit conventional beauty standards. It's rebellious and still subversive to be a woman who isn't ashamed of her body, who doesn't abide by the more negative messages we receive about our bodies and what we should do with them, or share them with. I think the difference between modern pin-up and some of Ferrier's work is primarily the audience and where the power ultimately lies. Modern pin-up still invites voyeurism, but often the subject of the artwork is the one inviting it, rather than having it put upon them without consent. It is an important shift in the dynamic, and imbues this genre with remarkable energy and power.

There seems to be a distinct feminist bent to some of Ferrier's domestic illustrations, with fed up housewives demanding an equal contribution to the household. How important is it to weaponise and satirise sexist cultures in your own practice?

It's very important to me in my own practice, as there is still a long way to go before everyone is treated equally. By creating these comics that 'say' something about the unfair treatment people receive, I'm not only creating relatable content so that people feel less alone, I'm also providing an outlet for frustrations felt and creating a community of people who care about these issues and want things to change. It's always a fun time when I get comments from someone who is riled up about one of my comics, which unfortunately comes with the territory. I tend to either give very little back, or tell them to keep scrolling. If it's incendiary, I'll delete their comment as I want my comments section to be a safe place for people who see themselves in my work. It's crazy that we're still fighting an extension of the same fight the housewives in Ferrier's work were fighting back in the 1950s.

As a send-up of married life, it's an effective illustration. Where do you see the future of pin-up going, in a post-Me Too world? Will female-led pin-up see a new creative boom as Western society sways further right-wing?

There was a lovely honeymoon period in the years after #MeToo when huge changes were seen in representation in advertising aimed at women, body positivity was being spotlighted on social media, and we also saw a huge surge of support for people of colour in 2020 with the Black Lives Matter movement. It felt like things were changing in a positive way - now I've begun to notice attitudes swinging back towards more conservative views. As a minor example, I have to watch which hashtags I use on Instagram as many of the tags associated with body positivity and the LGBTQIA+ community are banned. I'm battling the algorithms that seek to suppress this content more and more. I'm not sure where I see the future of pin-up art going in a post-MeToo world, as people (particularly women) still judge it as something dirty, or something only for men. They don't see the beauty or the artistry in it, they only see it sexually. That's really strange to me, as I primarily see the confidence and celebration of hyperfemininity; it actually isn't titillation that I see. I acknowledge that that may be what a viewer might get out of viewing my work, of course, and that's alright with me.

Honestly, I wish female-led pin-up would see a creative boom in Western society, but the alarming swing towards the right may lead to a crackdown on art that challenges conservative views. Pin-up art will undoubtedly survive in some form, but I'm not sure female-led pin-up art will see a surge in popularity - as it becomes harder to avoid censorship online, the authenticity of expression will be stifled. My art is now flagged if a pin-up has any cleavage on show, even if they are fully covered. I studied comics of the Spanish Civil War at university, and covered the censorship of comics under Franco in the postwar period as part of my research. As you might expect in a right-wing dictatorship, the censors were extremely conservative, with cleavages crossed out in a similar way as we're seeing today. The parallels are concerning, and I self-censor to a large extent, but it is becoming harder to create pin-up art as I wish it to be seen. I'll keep going though!

Biography

Hannah Rose is a British pin-up illustrator with a love for vintage comics of the 1940s-50s. Hannah is largely self-taught, becoming an illustrator after travelling the world as an internationally renowned burlesque performer. Hannah holds an MLitt in Comics Studies from the University of Dundee and was studying for a PhD in Spanish Comics before choosing to pursue the bright lights of burlesque instead. Hannah now creates pin-up art with inclusivity at its heart, providing a platform for pin-ups not often represented in vintage and modern pin-up art.

Follow Hannah on social media:

http://www.instagram.com/pillowtalkpinups

http://www.facebook.com/pillowtalkpinups