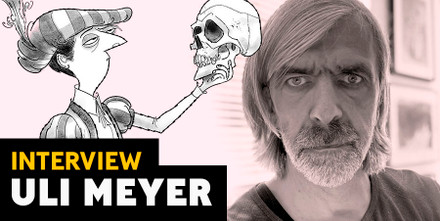

Uli Meyer interview

Posted by Heather Adamson on 2nd Aug 2022

Those who watch animated movies will probably recognise the titles Who Framed Roger Rabbit, American Tail and Space Jam. Those who don’t may still have heard about the reboot of Mary Poppins, Mary Poppins Returns, and the live-action remake of Aladdin. These films all have something in common: Uli Meyer, a talented German character animator/filmmaker based in London. Korero Press will soon publish The Lost Diaries of Nigel Molesworth, a collection of material originally published in Punch magazine, illustrated by Uli Meyer in the style of Ronald Searle, the original Molesworth illustrator. Uli graciously agreed to an interview to discuss his work.

Who are your inspirations?

Ronald Searle! And lots of other illustrators; there are too many to list. As a young animator, I was mostly influenced by the great Disney animators: Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, and especially Milt Kahl. I work in animation because I’ve always loved to draw, but I see myself as a filmmaker. I started making little films with a Super 8 camera when I was 10 years old. I’ve been greatly influenced by live-action movies, by the work of Hitchcock and Truffaut, and by dramas like

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. Animation is just one of many ways to tell a story, although animated films tend to be comedies. In my role as an illustrator and designer, Ronald Searle has always been my biggest hero, and I was lucky to meet him a few years before he passed away.

It seems that you made quite a big impression on Ronald Searle.

Back in 2007, a friend of mine, Matt Jones, asked me if I wanted to accompany him on a visit to Ronald Searle. Matt was living in the South of France at the time and found out that Searle lived in a little village called Tourtour. He contacted Searle by leaving a note at the local post office, and after an initial meeting, Searle invited Matt for lunch. He told him he could bring a friend, and that friend was me.

We went back for more visits in the following few years and were eventually invited to Searle’s house and studio. That’s when I showed him a 20-second animation test featuring one of his St Trinian’s schoolgirls. He told me it was the best animation of one of his characters he’d seen and that if I wanted to develop a film based on any of his characters, it would be fine by him. That’s how we ended up developing “Molesworth” with Lupus Films. Searle had and still has a huge influence on character designers everywhere, even if they’re unaware of it. So, letting me access his characters was, of course, a great honour, and I had a great responsibility to do justice to his work.

They say “never meet your heroes”, but Ronald was amazing, and we stayed in touch until his death in December 2011.

MOLESWORTH_TEASER_TRAILER from Uli Meyer on Vimeo.

How did Searle influence your illustration and animation styles?

Well, in animation, artists tend to simplify a design because we draw 24 images for each second of film. The approach to drawing is completely different when compared to illustration. An illustration tells the entire story in a single image, and one isn’t limited in the amount of detail and line mileage. The artists who created Disney’s 101 Dalmatians were inspired by Searle.

When I draw illustrations, I try to forget everything I learned in animation. I love drawing with ink. I was told that my own efforts are pretty similar to Searle’s, so it was fairly easy for me to mimic his drawing style for animation. There is, of course, effort involved when working with Searle’s characters, and there are those that you try to make as “Searlesque” as possible. It’s almost like copying someone’s handwriting; Searle’s style is unique.

I do want to stress, however, that whatever I draw will only ever be Searlesque. There’s only one Ronald Searle, and his drawings and wit are so distinctive that nobody could ever equal him. That’s why I’m amazed that people often confuse Searle with Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe. Both of those artists are very different to Searle, apart from in their use of ink splats.

Do you like the comedic aspect of Searle’s work?

Searle was a massive influence on postwar graphic humour, and his dark and anarchic wit, combined with his unique drawing style, has always appealed to me.

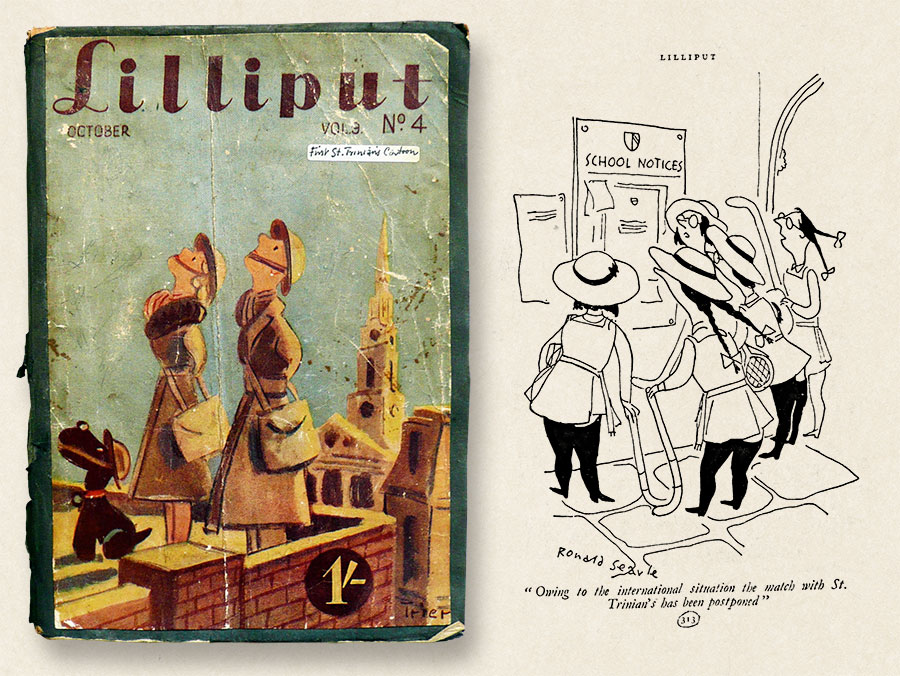

When Searle was 20 years old, in 1940, he sent a cartoon of a group of schoolgirls to Lilliput magazine. Before he got a reply, he was drafted into the army and flown out to Singapore to join World War Two. When he got there, he found a copy of Lilliput in the mud and leafed through it. There it was in print: the very first St Trinian’s cartoon. Soon after, Searle was captured by the enemy, and he spent the next four years in the infamous Changi prison camp. He told me that seeing his cartoon printed in Lilliput was what helped him stay alive. He continued to draw while many of his friends were dying around him, and he himself almost died. Imagine four years of witnessing death every single day. When Searle returned to England, his attitude was that nothing worse could happen to him. Every day was a gift.

Lilliput, October 1941, volume 9, no 4, cover by Walter Trier, in which the first St Trinian’s cartoon appeared.

After the war, he continued drawing the anarchic St Trinian’s cartoons, the dark humour often reflecting the horrors he’d experienced in the prisoner-of-war camp.

You’ve pitched a few projects that weren’t accepted by studios. How do you deal with disappointment when you aren’t able to get a project off the ground?

If you have an idea, you can be sure that lots of other people elsewhere have had a similar one. But that doesn’t put me off because studios sometimes develop a project, and then it never happens. So, I keep pushing. And then years go by, you spend a lot of time, money, and energy on something, and it’s never realised. It’s difficult sometimes, but what can you do? I have fun along the way, but of course, it’s a disappointment when it doesn’t happen.

What advice would you give those who are trying to break into the animation industry?

If you want to succeed in animation, you must really love it. Don’t study animation just because it sounds cool. If you don’t put everything into it – all your time, effort, and love – you won’t get anywhere. I’ve known people who got into animation because they thought it was a cool idea but then really didn’t put the work in. Most animators are very passionate about what they do, so there will be lots of competition, but if you’re good, it’s a great time to be in animation.

Are there factors that make the animation industry particularly difficult to break into?

You have to get to know people. You have to mingle. As I’ve said, being passionate about your work is very important, but that’s not enough. You must be able to get out there and approach people, talk to people. A lot of artists are very introverted, and they find this difficult to do and aren’t necessarily good at it; that said, I know quite a few artists who are so brilliant that, even though they’re introverted, they still broke through. Unfortunately, a lot of schools and courses don’t teach you this aspect of getting into the business.

In fact, I’m one of those artists who’s not very good at meeting people, so you can imagine how nervous I was about meeting Searle, but that turned out great.

Would you consider drawing a therapeutic exercise?

Oh yeah. I think drawing is therapeutic for every artist because you’re sort of in your own little world. You can hide away. You can work through things, especially in animation, since it’s such a laborious, time-consuming process. And I think that this must have been the case for Searle, too, using drawings to work through past experiences.

I’m getting too old to work long days now, but when I was younger, animating was like an addiction. I’d work late into the night and couldn’t wait to get up in the morning to continue. People usually ask if it’s boring to do the “same drawing” over and over again, but it isn’t. It’s very exciting. You know, sitting there drawing, making characters come alive. It’s magical.

How do you cope with challenges or when there’s a slump that you can’t work through?

I distinguish between creating work for a client and creating work for yourself. Working for a client, you’re less likely to go through a slump. I have decades of experience and am very professional. I’ve worked on many high-profile projects for Disney, Warner Bros and other major studios, and the task is always very clear. There’s a plan and a reason for the project. I know precisely what needs doing and how to do it well.

I find that working on my own stuff is often more of a challenge. The slump happens when you question the point of it all and whether it’s good enough, which it never is. When that happens to me, I pause and do something else.

You’ve been working with Korero to produce illustrations for The Lost Diaries of Nigel Molesworth. How has that experience been for you?

I think there were originally four Nigel Molesworth books, but then earlier Molesworth material – diary entries that had appeared in Punch magazine – was rediscovered. Robert J. Kirkpatrick, who put together a collection of those diary entries, asked me to do a cover for an Amazon print-on-demand version of them, and that was quite successful. Then Korero contacted me as they thought it would be great to do a proper book of the diaries. They asked if I’d be interested in producing the illustrations for that, which of course, was great.

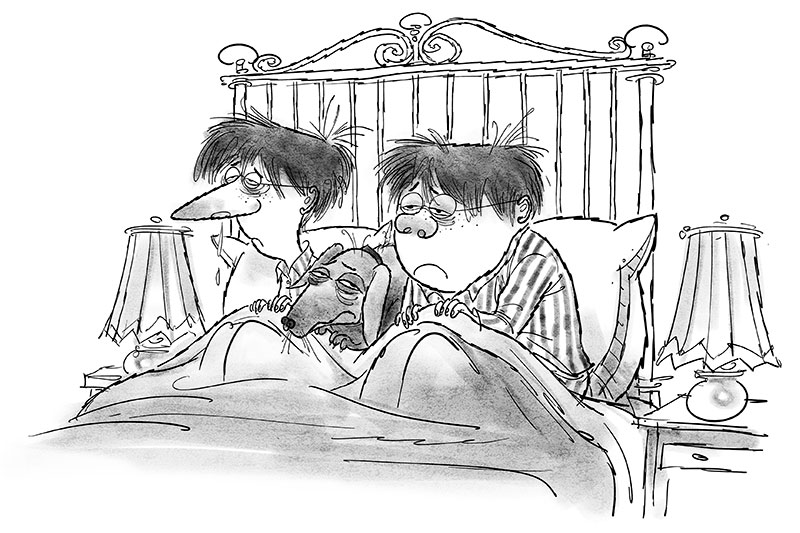

All in bed with colds.That is life.

I would have loved to have done the illustrations with ink and paper. However, I have a two-year-old, so I decided to create them digitally, whenever I had the time. They still look like ink drawings, I think, and are quite close to the Searle style. I’m not sure if they’re as witty as his, but there you go!

Why did you choose to work with Molesworth? Was it the writing, or because it was Ronald Searle’s work?

To be perfectly honest, it was Searle’s work, mostly. I started reading the Molesworth books, which was very hard work because English isn’t my mother tongue, but I got into the project largely because of Searle’s illustrations. There are great characters in the writing, but there are also great characters in the drawings. Grimes the headmaster, for example, and of course, Molesworth himself.

What was the most challenging aspect of creating the illustrations?

Next to me on my wall is an original page from one of the Molesworth books, a drawing by Ronald Searle. I sit here and I draw, and then I look over at the original. Some people don’t see the difference, but I do.

Searle’s way of drawing was ingenious – he was just writing these things down. It was just him. You know his drawings are him, so you try to mimic them. But actually, you can’t do that – you can only come close. I always say it’s Searlesque or Searle-ish, but it can never be Searle.

Some people say, “why didn’t you just do your own thing?” But you know, I was trying to stay as close to Searle as possible, to his style, especially given that the diaries came before the books.

What did you enjoy most about working on Korero’s The Lost Diaries of Nigel Molesworth?

The chance to invent new characters. That was a good experience. In the

Lost Diaries, there are characters that don’t appear in the later books, so I was asked to show new designs for characters that don’t exist in Searle’s style, which was great fun to do.

Gran now making munitions in xplosives factory

If you look at Searle’s Molesworth drawings, Molesworth himself looks different in every single drawing. It’s a funny thing because if you try to analyse a drawing, you go by proportions: shorter forehead, bigger face, the size of the nose. With Searle’s Molesworth, every drawing is completely different, but you always recognise it as Molesworth. That’s something very intriguing. So, you do your own version of that. You think you’ve figured out what Molesworth is, and then you realise, well, there are no rules.

To buy your copy of The Lost Diaries of Nigel Molesworth click here.