Wallestein the Monster

Posted by Adam Twycross on 16th Apr 2020

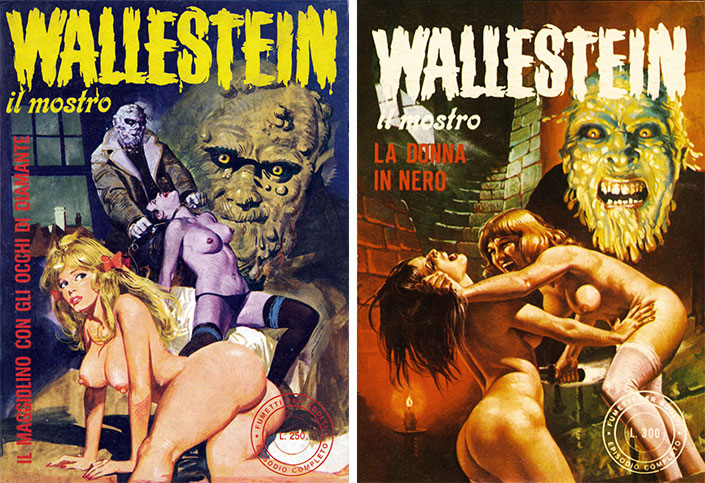

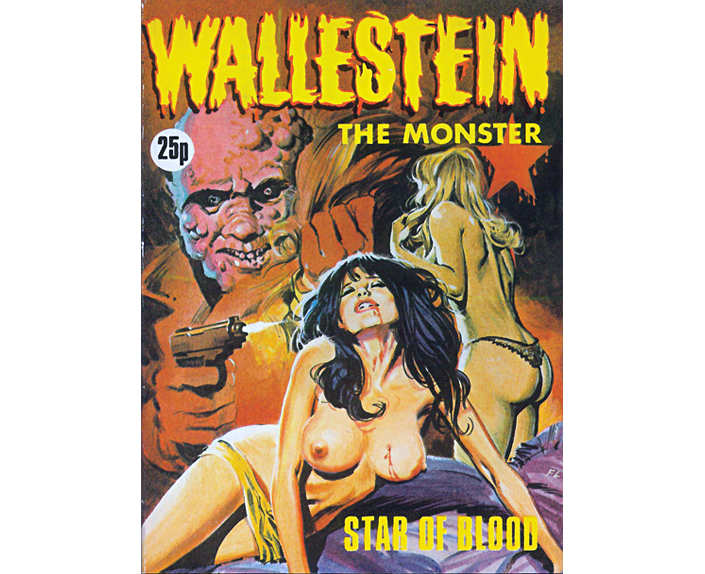

Wallestein the Monster, which appeared on Italian newsstands between 1972 and 1982, was one of the many pocket digests produced by the Italian publisher Edifumetto that offered readers a heady mix of gothic horror, fantasy, sex and violence (figs 2-4). Wallestein’s was a world in which the gothic and the contemporary intertwined. Ruined castles, deserted cemeteries and grotesque monsters collided with a world of fast cars, guns and glamour in stories that revelled in depictions of sex and violence that were filtered through the symbols and structures of the gothic imagination. Each issue featured a self-contained story of around 120 pages, with lush fully painted covers, and bold black and white interior art, typically with two panels to a page. Although the series was successful internationally, with the character appearing in France and South America as well as its native Italy, Wallestein is now largely forgotten in the English-speaking world.

The Elements of Wallestein the Monster

The series’ narrative revolved around the exploits of the aristocratic Jimmy Wallestein, whose dashing good looks and affluent lifestyle masked a terrifying secret: that the real Jimmy was long since dead, and his place had been taken by a beast of terrifying power who wore a special mask to hide its true features. His was, in the words of the comic itself, “un volto che significa orrore, paura, incubo, libidine”, or “a face that means horrors, fears, nightmares and lust!”.

Wallestein was certainly a compelling character and a character of extremes. Although on the surface appearing to be the very model of refinement and control, Jimmy’s cultivated image was a literal mask that disguised an unrestrained appetite for sex and violence. As such, Wallestein’s barbaric alter-ego can be understood as a powerful fantasy figure that spoke of the very human desire to cast off the constraints of civilised society and indulge our most primal and universal urges.

Yet for all the unbridled carnal and physical excess that Wallestein exhibited when in his monstrous form, he did not entirely lack control. His victims were not random, and his actions conformed to a clearly codified moral system that centred around the need to protect and avenge the weak and dispossessed. Wallestein’s recurrent subtext revolved around the inability of capitalist societies to prevent the subjugation and exploitation of the weak by the powerful, and it was in this capacity that Wallestein acted as a great leveller of human suffering. In L’Assassino Colpisce Quattro Volte (Barbieri 1973b), for example, Wallestein tracked down and murdered four members of a wealthy family who had murdered a young woman for financial gain. A similar lust for material gain drove the narrative of La Stella Di Sangue (Barbieri 1973), in which rape and kidnap were used as tools in a wider criminal enterprise and which Wallestein avenged in typically bloody fashion. The motive of the villain of L’Amante Delle Vergini Morte (Barbieri 1972) was darker still, but the plot still centred around the exploitation of the weak by the socially privileged. Here Wallestein’s investigation into the desecration of fresh graves uncovered the fact that the culprit was a deranged aristocrat who had murdered his adopted daughter to indulge his necrophiliac urges upon her corpse. The extremes of Wallestein’s behaviour were not simply gratuitous, therefore, but proportional to the world in which he operated. His refusal to limit his behaviour can be understood as being emblematic of a wider repudiation of the need to conform to the standards of a society that had long since proved itself incapable of protecting those most in need.

Wallestein’s wider cast provided the narrative framework required to articulate such themes. Although the self-contained nature of the stories meant that the series featured a changing roster of adversaries and opponents, it was the police, in the guise of the bungling Inspector Fleming and Sergeant Blackman, who most frequently acted as the principal antagonists. Wallestein’s flagrant disregard for the law and frequent bouts of brutal violence were justified within the series’ moral framework; such nuance, however, was beyond the imagination of two characters whose narrative function was to represent the forces of corrupt and inefficient societal control. Correctly surmising that Wallestein was behind a raft of unsolved thefts and murders, Fleming and Blackman’s obsession with proving his guilt typically blinded them to the very existence of the greater crimes that he himself was investigating. Beyond these two adversaries, a more intermittent antagonistic presence was that of Wallestein’s arch-nemesis, the villainous Scorpion. A controlling force who used a network of lesser criminals to conduct his operations, the Scorpion’s visual design created a pictorial link that embedded him firmly within the iconography of capitalism, the adverse social effects of which lay at the heart of Wallestein’s thematic construction. Resplendent in a suit and bowler hat, and usually smoking a large cigar, the Scorpion acted without compunction and thought nothing of using the rape and murder of innocents as a vehicle through which he could enhance his wealth and power.

Wallestein was aided in his adventures by two key female characters, the first of whom was his girlfriend, the beautiful and sexually adventurous Sara Orloff. Narratively speaking Sara was a rather simple character whose role was often limited to that of the prototypical ‘damsel in distress’, or the facilitator of sex and narrative exposition. Despite having been a lover of the original, ‘real’ Jimmy Wallestein, Sara had dealt with his death with remarkable ease and was now a willing lover of his monstrous replacement; indeed she gained as much pleasure from copulating with him as a beast as she did when he was disguised as a handsome playboy.

A more intriguing character was Wallestein’s female mentor, Olympia Moore. An apparently harmless old woman, Olympia was nevertheless a mysterious figure who had access to a secret and extensive network of informers and operatives, allowing her to act as a source of privileged information. Her motives were cryptic, but she seemed to share, or perhaps to drive, Wallestein's desire to protect and avenge the weak. In some stories, Olympia simply provided the support and information necessary for Wallestein to complete his mission, but in others would summon him and inform him that a crime had been committed and that vengeance was required. Despite being a member of the supporting cast, Olympia can, therefore, be understood as a controlling force for Wallestein. In many cases, she was the true instigator of narrative events. She also played an important role in the character’s origin story, as the character who first found and housed the beast following the death of the real Jimmy Wallestein, and the individual who introduced him to the beautiful scientist Alice Wolff, who created the special mask with which the beast is able to hide his true appearance.

Wallestein’s recurring cast, therefore, represented a gendered system in which the dichotomy of good and evil was articulated through the narrative positioning of men and women; the beasts’ principal enemies were male, whilst his allies were female. Within individual stories, however, this gendered construction became less apparent; although many stories revolved around the beast avenging or protecting a female victim, the aggressors and perpetrators of crime were just as likely to be female as they were male. Women, moreover, were just as likely to be subjected to Wallestein’s brutal violence, even if they had only unwittingly impeded his rampaging vigilantism.

Wallestein’s Influences

Wallestein shows clear influences from other Italian media of the period and has particularly close links with giallo, the genre of Italian cinema that first appeared during the mid-1960s and whose heyday of the 1970s was directly contemporary to Wallestein’s appearances. The term giallo, Italian for yellow, originates from the cover colour of a series of noir mystery novels published by Mondadori that were popular in post-war Italy. Whilst the stylistic boundaries of giallo cinema are difficult to identify in absolute terms, and a precise definition, therefore, remains elusive, several genre characteristics can be identified that apply as much to Wallestein as they do the wider giallo movement. Gialli often reflect cultural anxieties concerning the fragmentation of traditional social structures brought about by increased urbanisation and the march of capitalism; many examples consequently feature themes of alienation from wider society, and protagonists who seek to “impose order on a world disordered by social change” (Mackenzie 2015). In presenting its central character as a champion of the oppressed in a modern world where the acquisition of material wealth has taken precedence over moral decency, Wallestein can be read as an articulation of precisely the same cultural fears.

Many gialli, such as Mario Bava's iconic Blood and Black Lace, also feature an archetypical image of a killer whose true features are hidden by a mask, trench coat, and gloves, providing a template that matches Wallestein’s character design almost exactly. Other genre signifiers, such as frequent scenes of female nudity and brutal, sexualised violence, are similarly common to both giallo and Wallestein. It is in Wallestein’s cover art, however, that the clearest visual link to the giallo movement can be seen. Many gialli, and in particular the films of Mario Bava and Dario Argento, are notable for their use of an intense, highly saturated colour palette that results in a visceral and impressionistic visual style. Wallestein’s two most famous cover artists, Alessandro Biffignandi and Emanuel Taglietti, used a strikingly similar palette to give their cover paintings a dramatic and intense visual flair that perfectly encapsulated the themes and content of the series.

Beyond such cinematic inspirations, Wallestein also exhibited a clear influence from other comics. The character’s origin story, for example, focussing as it did on a character whose death precipitates the arrival of an avenging swamp beast, is clearly inspired by Swamp Thing, which premiered in DC’s House of Secrets #92 (Wrightson 1971) just months before Wallestein’s first issue. Likewise, the central premise of a playboy millionaire who secretly fights crime in the guise of a secret alter-ego owed a clear debt to Bob Kane’s Batman. Whilst Wallestein, therefore, exhibited some narrative similarities with American comics, the title’s frequent depictions of sex, nudity and extreme violence were facilitated by the various changes that had been underway within the domestic Italian comics market over the previous decade. A pivotal moment in the international evolution of adult comics had occurred in 1962 when sisters Angela and Luciana Giussani had created Diabolik, widely regarded as the first adult-oriented Italian comics title (Castaldi 2010, p.13). Although the eroticism and violence in Diabolik were relatively tame compared with the excesses that would follow, the title nevertheless established a template that many Italian comics, including Wallestein, would follow. Like Wallestein, Diabolik appeared in a pocketbook format and featured a masked anti-hero who, aided by a beautiful female lover and confidant, operated above the law and in opposition to the official police force. Moreover, in proving the viability of comics aimed at adult audiences, Diabolik paved the way for a massive boom in similar titles that swept onto the Italian market through the first half of the 1960s, gradually increasing the levels of sadistic violence and eroticism that were permissible as they did so. By the early 1970s depictions of outright nudity and extreme violence were no longer enough in themselves to preclude nationwide distribution through newsstands, and it was in this climate that Renzo Barbieri, a writer who had previously worked as a scriptwriter for adventure comics, founded Edifumetto. Alongside Wallestein the Monster, Barbieri published a raft of other titles that straddled a broad range of adult content, including Candida la Marchesa, a slice of historical erotica featuring a beautiful noblewoman turned thief, Sexy Favole, which featured erotic re-imaginings of classic fairy tales, and Biancaneve, a bawdy reimagining of Snow White with attractive art supplied by Leone Frollo.

Wallestein in Britain

Although not without controversy, the gradual normalisation of erotic content within the Italian comics market mirrored the wider social process of liberalisation that was being felt across a range of media, and indeed wider society, at a transnational level. In Italy, the pioneering Men magazine appeared in 1966, becoming the first Italian magazine to follow Playboy in the United States, He and Adam in France, and Penthouse and King in the UK to include photographs of topless women in its pages. In 1962, the year of Diabolik’s debut in Italy, France saw the arrival of Barbarella in the pages of V magazine, and in America Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder’s Little Annie Fanny began its run in Playboy, in the process becoming the first multi-page erotic comic to appear in a major American publication. It is often claimed that British comics remained insulated from this process of international liberalisation and that, with the notable exception of the ‘underground comix’ whose production was inherently linked to the hippy counter-culture, the mainstream UK comics market remained resolutely juvenile until at least the 1980s (Barker 1989; Sabin 1993; Chapman 2011).

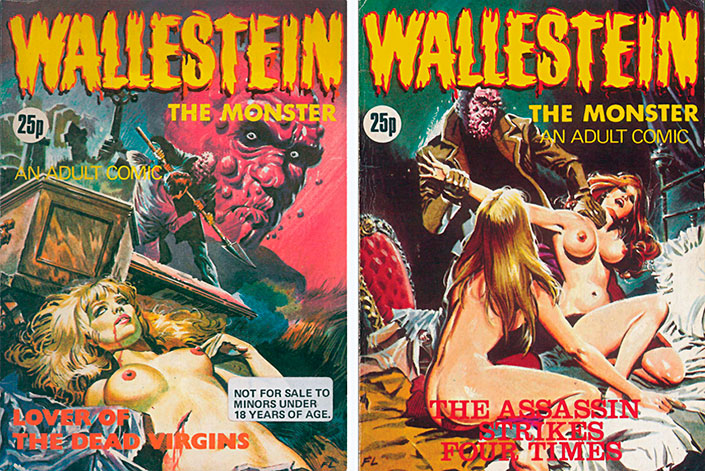

Although the roots of this misconception are beyond the scope of this article, its veracity is neatly repudiated by the fact that not only Wallestein the Monster but also Sexy Favole, Biancaneve and Candida La Marchesa all appeared in Britain during the mid-1970s, where they received wide distribution and were available to buy from newsagents across the country. The fact that the violence and erotica of these titles represented the very limits of permissibility anywhere in the international mainstream is indicative of the degree to which Britain was active in the evolution and proliferation of adult comics during this period (figs 5-6). The nationwide distribution of Wallestein and its sister titles similarly refutes the common claim that the ability of British comics to reach beyond juvenilia was constrained to a significant degree by the dominance of the major distribution chains. Sabin (1993, p.45), for example, suggests that the reluctance of networks such as that operated by W.H. Smith to distribute adult comics during the 1960s and '70s effectively precluded British involvement in the adult comics boom that was then gathering pace across Europe.

The chronology of Wallestein’s British appearances indicates the speed with which such material was seeping back into the British comics market. In all, three issues of Wallestein- Lover of the Dead Virgins, The Assassin Strikes Four Times and Star of Blood appeared in the UK, all of which had originally appeared in Italy as part of the comic’s second series between December 1972 and February 1973 . Although the British issues were neither numbered nor dated, the advertising contained within them indicates that they saw print soon after their Italian counterparts, almost certainly over the winter of 1974-75. It is also clear that Wallestein, Candida, Snow White and Sexy Tales! were published simultaneously as three blocks of four titles each since each one carried an advertisement to cross-promote the remaining three titles in the series.

The publisher information carried in each of the books is also enlightening, and a full analysis indicates the complex arrangements that major mainstream publishers were using at the time to capitalise on the emerging market for comics erotica whilst simultaneously insulating their other publications from any direct association. The publication information for the British reissues of Wallestein indicates that they were produced by Top Sellers Ltd, whose business address was listed as 135 Wardour Street, London. This is misleading, however, for at the time of publication this address was the London home of Warner Brothers, and Wallestein was, in fact, a Warners publication. During the 1970s a huge range of material was produced from their Wardour Street offices, with different titles using both different distribution methods and a variety of company names depending on their genre, market, and potential to cause reputational damage.

This had been facilitated by Warner’s gradual acquisition of a range of smaller publishing firms, many of which had established credentials in particular fields of publishing and had often established their own independent distribution networks prior to being bought out. Top Sellers was one such firm, having grown out of a 1950s printing and publishing company that had amassed its own fleet of wholesale vans which delivered direct to newsagents, thus bypassing the established networks of W.H Smith and its various competitors entirely. Their subsequent takeover by Warner Brothers had made the company a subsidiary. Still, its distribution network remained intact and was leveraged as a means through which Warners could produce and disseminate adult material without the risk of cross-contamination to the rest of their publications. Along with Wallestein and its sister titles, Warners also used the Top Sellers brand to publish pornography magazines such as Cinema X, and Parade, whilst numerous other genres were produced through a variety of entirely different brands. As Dez Skin (2016) notes, these included Brown and Watson, which was used to produce hardback children’s annuals, Thorpe and Porter, under whose banner American comics from DC, Marvel and others were reprinted for British audiences, and Williams, which was used for co-productions with various European partners.

Despite the fact that Wallestein, Candida, Biancaneve and Sexy Favole only gained a brief foothold within the British market, their very existence in the UK is highly significant, therefore, and allows for a fuller picture to emerge of the ways in which adult comics were being produced and disseminated in the UK during a key period of transnational evolution. The presence of such titles in Britain is also indicative of a deeper and more extensive interconnection between British and European comics production during the 1960s and 70s than is commonly understood. It hints at the very active role that British comics were playing in the development of adult comics internationally.

If you want to find out more about comics such as Wallestein the Monster, take a look at the series of Sex and Horror books published by Korero Press.

References and Bibliography

Barbieri, R., 1972, ‘L’Amante Delle Vergini Morte’, Wallestein Il Mostro v2 #1, Milan: Edifumetto.

Barbieri, R., 1973, ‘La Stella Di Sangue ’, Wallestein Il Mostro v2 #3, Milan: Edifumetto.

Barbieri, R., 1973b, ‘L’Assassino Colpisce Quattro Volte ’, Wallestein Il Mostro v2 #3, Milan: Edifumetto.

Barbieri, R., 1974, ‘Star of Blood ’, Wallestein the Monster #1, London: Top Sellers.

Barbieri, R., 1975a, ‘The Assassin Strikes Four Times ’, Wallestein the Monster #2, London: Top Sellers.

Barbieri, R., 1975b, ‘Lover of the Dead Virgins ’, Wallestein the Monster #3, London: Top Sellers

Barker, M., 1989, Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Biffignandi, A., 2016, Sex and Horror: The Art of Alessandro Biffignandi, London: Korero.

Carcupino, F., 2019, Sex and Horror: The Art of Fernando Carcupino, London: Korero.

Castaldi, S., 2010, Drawn and Dangerous: Italian Comics of the 1970s and 1980s, Jackson, MS: The University Press of Mississippi.

Chapman, J., 2011, British Comics: A Cultural History, London: Reaktion Books.

Mackenzie, M, Gender and Giallo, 2015, In: Blood and Black Lace Special Edition Dual Format [film, DVD]. Directed by Mario Bava. Italy: Emmepi Cinematografica/Les Productions Georges de Beauregard/Monachia Films.

Sabin, R., 1993, Adult Comics: An Introduction, London: Routledge.

Skinn, D., 2016, Warner Bros (Williams)

Taglietti, E., 2015, Sex and Horror: The Art of Emanuele Taglietti, London: Korero.

Wrightson, B. and Wein, L., 1971, ‘Swamp Thing’, House of Secrets # 92, New York: DC Comics.